Image: TECHNOLOGICAL DREAMS SERIES: NO.1, ROBOTS, 2007, Anthony Dunne & Fiona Raby

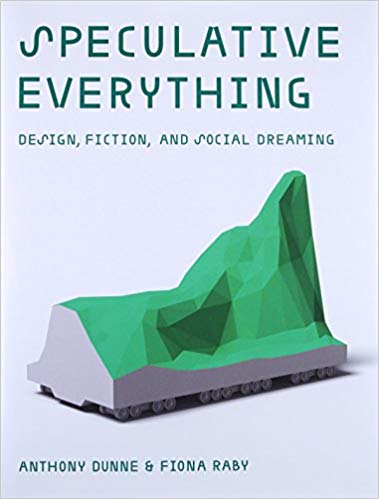

It all started with reading through the book “Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming” by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, published in 2013. There it was: the provocative, fun, subversive, the critical, the challenging of assumptions – everything functional, everyday design was not. I absolutely loved it – it inspired the rest of my PhD work and injected a much needed new direction and enthusiasm into my work.

Image: Speculative Everything, 2013

The question that came to my mind was how we could use designed objects into provoking people into critically reflecting on what was being designed. This is an incredibly valuable tool, in particular when we think about how technology is developed today – usually as a social experiment involving some piece of new technology and people using it. This type of technological determinism, the assumption that just because we can build it, we should do so, irrespective of the impact and consequences this might have on people and society, is showing increasing signs of strain in recent years. Think of the Facebook scandal surrounding Cambridge Analytica, where it emerged that Facebook users’ data was illegally harvested to target them for political advertising. Or remember Google’s experiment with Google Glass, a wearable smart glass that would allow users to secretly record video footage of anyone? Yes, it wasn’t such a great idea, people hated it due to privacy concerns and it was mothballed.

So could there be another way of thinking about the potential issues with the development of technologies before these actually arise?

In contrast to commercial design practices, critical & speculative design and design fiction are critical design practices that are about finding rather than solving problems, and about opening up opportunities for critical reflection and discussion. Critical design “uses speculative design proposals to challenge narrow assumptions, preconceptions, and givens about the role products play in everyday life” (Dunne & Raby, 2013). These approaches challenge design practice itself. It also involves a broader perspective by integrating and considering the wider social, cultural and ethical implications and context of design.

However, these approaches differ in the sense that critical design itself is often associated with its inventors, Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, who developed this concept at the Royal College of Art in London.

Image: TECHNOLOGICAL DREAMS SERIES: NO.1, ROBOTS, 2007, Dunne & Raby

“One day, in the future, robots will do everything for us. It’s a dream that refuses to go away. Over the coming years, robots are destined to play a significant part in our daily lives — not as super smart, functional machines, nor as pseudo life forms, but as technological cohabitants” (Dunne & Raby, 2007).

The resulting artefacts were mostly exhibited. One of the most important exhibitions was for example the exhibition “Design and the Elastic Mind” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 2008.

Image: Museum of Modern Art, 2008, Universal Everything

However, Tonkinwise has also offered a critique of the fact that critical design artefacts are often to be found in museums, rather than questioning design practice. This would require to move critical design out of the gallery space into real life settings, where critical objects allow interactions for the purpose of systematic enquiry resulting in actionable insights. Tonkinwise argues that “this kind of generative foresight certainly does not come from contemplating a removed museological object. If these things are props, it is because you must play with them, performing in improvisatory ways” (Tonkinwise, 2014). Malpass argues that in his book “Critical Design in Context” (2017): “Critical design and art may or may not overlap. But that critical design, tactically speaking, should not be absorbed into the social practices of the artworld, with their institutional structures of exhibitions, museums, and funding. Rather, critical design works best when it is operating within a context of use” (Malpass, 2017).

As Wakkary et al. show, functional artefacts situated in everyday settings are a meaningful site of critical enquiry (Wakkary et al. 2015). Wakary et al. placed critical artefacts exploring user’s attitude towards autonomous behavior of technology in participants’ homes.

Image: Wakkary, 2015. Rudiment #1 is a small machine that was attached magnetically to a surface and moved autonomously.

Khovanskaya et al. created an extension to Google Chrome’s web browser in order to explore issues of online privacy. The interface was deliberately designed as ‘strange’, ‘creepy’ and ‘malfunctioning’ with the purpose to provoke participants (Khovanskaya, 2013). These are examples of critical design practice which shows critical artefacts in use, and therefore, interactive artefacts may have a greater chance to succeed in prompting people to think about issues under investigation.

Malpass distinguishes between speculative and critical design in the sense the he argues that speculative design is about technological themes and is concerned with the projection of sociotechnical trends through developing technological scenarios of products of the future. Critical design, however, focuses on “present social, cultural and ethical implications of design objects and practice” (Malpass, 2017) and therefore offers a critique of what already exists.

But, given the immense controversy surrounding many technologies today, from social media platforms, to algorithms to robotics, it is perhaps time to integrate these perspectives as well as using them as a research tool within commercial design practice to investigate potential problematic features and scenarios before these make it into products and software. So far, there is little sign in industry of a willingness to approach design differently, but the example of the recently failed AI ethics board of Google clearly demonstrates a need to expand current commercial design practice.